→ gennaio 28, 2015

after forming his coalition yesterday, Alexis Tsipras will present his cabinet today, with Yanis Varoufakis set to become the next finance minister and Independent Greeks leader Panos Kammenos defence minister;

The coalition deal with the Independent Greeks signals an uncompromising stance towards Greece’s lenders;

Independent Greeks support the key planks of Syriza’s Thessaloniki programme;

Kammenos gave green light to legislation already prepared, which is ready to go in a first blitz of legislative action by the new parliament;

the first bill raises the minimum wage back to €751 and reintroduces collective wage bargaining;

the second bill is on tax debt with new repayment plans, so that no more than 20%-30% of taxpayers’ annual income is used for repayment;

Other bills may be introduced later, include the end of the civil service mobility scheme and free electricity for poor households;

The primary surplus, meanwhile, shrunk last year, mainly due to revenues falling behind target;

Further News

The eurogroup gave a poker-faced response to the new Greek government – nothing changes, pacta sunt servanda;

officially Europe is a firmly opposed to a haircut, but is open to talks about other issues;

France sees its opportunity to become consensus seeker in Europe;

Wolfgang Munchau says a compromise should be easily achievable but this would require a shift in German policy, which he does not see;

Paul Krugman says that flows matter in the case of Greece, not stocks – the priority must be to get the primary surplus down;

Mark Schieritz agrees, and says Syriza would be ill-advised to insist on a haircut;

Reza Moghadam disagrees: there is no hope for Greece without a haircut and a cut in the required structural surplus;

We agree with Moghadam – stocks matter a lot because of the EU’s institutional arrangements;

Kevin O’Rourke says that if Syriza caves in to the EU, the Greeks would be voting for more radical anti-European parties next time;

Snap elections in Andalusia, Spain’s largest region, will set the tone for the confrontation between PSOE and Podemos over the rest of the year, and affect the PSOE’s internal leadership struggle;

Karl Whelan says it is far from clear that the ECB can direct an NCB to buy certain bonds, and if it can, it is far from clear whether it will use its powers;

The car rental company Sixt, meanwhile, says that despite QE it is still in a position to offer rental cars for under €1tr a piece;

Alexis Tsipras has been sworn in as the new prime minister and is to present his cabinet today, with Yanis Varoufakis set to become the next finance minister and Independent Greeks leader Panos Kammenos defence minister. Both Tsipras’ choice of the Independent Greeks as a coalition partner and the first bills in the pipeline suggest a bold move against the troika and the terms of the bailout agreement.

The alliance with the Independent Greeks is also a risky strategy for Tsipras, writes Macropolis, as the party is rabidly critical of Greece’s lenders and famously erratic. By opting for Kammenos as his coalition partner, the new Greek prime minister seems to be sending a message to lenders that he is not willing to compromise his position with regard to ending the bailout and securing debt relief. The risks are just too high for Tsipras, as he will have no one else to blame at home for any compromise he may have to strike with the EU lenders.

As for the coalition agreement, it was more straightforward than one would have thought. Sources told Kathimerini that the Independent Greeks agreed to back Syriza’s economic policies, as set out by Tsipras at the Thessaloniki International Fair in September, as long as the new prime minister does not forge ahead with changes in areas where Kammenos’s party has objections, including foreign policy issues and plans for a separation between the Church and state (Tsipras is the first prime minister to be been sworn in without a church ceremony).

Kammenos gave a green light for legislation already prepared. The first bill is to raise the minimum wage back to €751 and reintroduce regulations regarding collective wage bargaining, according to Kathimerini. The second draft law will focus on measures for taxpayers to be given better terms to repay overdue taxes and social security contributions. The bill foresees new payment plans, so that no more than 20%-30% of taxpayers’ annual income goes toward repaying their debts. The new government also wants to pass legislation that will end the mobility scheme and evaluation process in the civil service. This will lead to some people who have lost their jobs as a result of these measures being rehired. Other measures expected in the coming weeks are legislation that would allow some 300,000 households under the poverty threshold to receive free electricity. Tsipras is also due to push for the reopening of public broadcaster ERT, which was shut down in June 2013.

The latest data suggests that the primary surplus shrank by €1.7bn in December, according to Macropolis. The final figures for the whole year show that revenue (excluding tax refunds) fell short of target by €3.18bn, while expenditure was €769m better than target and the portfolio investment balance was €206m lower than expected. The revenue shortfall includes the €1.9bn income from SMP profits, which was not collected as the troika review was not concluded.

What to make of Syriza

The eurogroup is clearly not yet prepared for any of this. The new Greek finance minister was not yet present, and everybody stuck to their previous lines. Pacta sunt servanda. Greece has to abide by existing agreements. We spare you the specific quotes. We would like to urge readers to take all these comments with a grain of salt. Of course, the creditors would not signal any shift in their position ahead of a lengthy period of negotiations that lies ahead. More important is that they will negotiate in good faith. We are not so certain after we heard Wolfgang Schauble saying that nobody forces anyone into a programme: If Tsipras finds the money elsewhere, then good luck. While a lot of the comments should be seen as tactical posturing, the rejection of a haircut, however, seems to be non-negotiable, at least at this point. The article says the most probable path of action is a temporary extension of the current programme.

The French see this as an opportunity for France, with commentators rejoicing the fact that Syriza’s victory rattles on the dogma of the so-called Euro-liberalism. France might also try to redefine its political role of consensus-seeker in Europe. Several commentators spoke of a “historic responsibility” to reconcile Greece and Germany, southern and northern Europe, finds the Irish Times. As for the IMF, Christine Lagarde sounded uncompromising in an interview with Le Monde, saying “there are internal rules within the euro zone to be respected. We cannot make special categories for specific countries.”

The view from Berlin is more sceptical. FAZ quotes a government official as saying that it is going to be difficult if Tsipras does what he promises. In his Spiegel Online column Wolfgang Munchau writes that the situation is very dangerous. It is hard to see everybody meeting half way and still be able to pretend that they are true to their positions. The best outcome would be a shift in the German position. But years of ordoliberal indoctrination have dramatically raised the chance of a major accident. The German public and the media are not prepared for this. He said that a rational agreement should, in principle, be possible, the probability that one of the parties, or even both, miscalculate is very high.

Paul Krugman and several other commentators yesterday made the points that it is flows that matter, not stocks. The Greek debt stock looks high, but should not be a priority now since most of the debt is official. The real killer is austerity. Krugman does the multiplier math on what would happen if Greece were allowed to spend its entire €4.5bn primary surplus – the answer is a reduction in the unemployment rate by some 10pp.

Mark Schieritz makes the same point. The debt-to-GDP is irrelevant since the official debt does not need to be repaid until 2022. There are no interest rates on the EFSF credits, and the average interest rate on all loans is lower than Germany’s. Instead of focusing on debt, one should talk about the fiscal restrictions. He writes the Greeks would be ill advised to focus too much on the issue of debt relief.

Reza Moghadam says stocks matter. He says the best hope is for a quid-pro-quo deal – the EU should agree to halve Greek debt, and to halve the required fiscal balance, in exchange for structural reform. He says that Syriza may be more willing to accept reforms than the previous government.

It is worth reading Jamie Galbraith on all of this. He has been a co-author with Yanis Varoufakis, the new finance minister, and his views represent those of the Syriza administration on those points.

Kevin O’Rourke makes the broader point that the EU would be ill-advised to ignore the sentiment that is behind Syriza’s success.

“Syriza is opposed to European macroeconomic policy, and won the elections on that basis. They speak for lots of Eurozone voters, not just Greek ones. If the EU have any sense they will not play hardball with the new Greek government, especially since just about everyone agrees that Greece’s debt is unsustainable. Nor should anyone be hoping that the new Greek government will be “pragmatic”, and forget its opposition pledges once in government. The Greeks want fundamental change, and have voted for a democratic pro-European party to express that desire — which, you might think, is a lot more than the Troika deserves. If Syriza doesn’t deliver, for fear of upsetting its Eurozone partners, voters may turn to parties that really are anti-European. In the Greek context, that could be very ugly indeed. How the EU responds to last night’s election will tell us a lot about the actually existing European project.”

Stocks matter in this particular context because of the EU’s fiscal rules and the programme math. We understand the point about the present value of Greek debt, and the i/r moratorium until 2022. But without a write-off of debt, Greece will be forced to run much larger surpluses than what would be necessary after a haircut. Even when Greece were to exit the programme, the country would still need to abide by the EU’s fiscal rules. Getting from 175% to 60% of debt in 20 years requires much higher primary surpluses than getting there from 90%. So if you are serious about a lower primary surplus, don’t miss the level of debt. Much of this stocks-vs-flow debate is based on an ignorance of European political, legal and institutional settings.

The significance of early regional elections in Andalusia

The combination of QE and Greek elections has drowned the news of yet another early election in Spain which despite being limited to the Andalusian region could have national political implications.

The elections called by Andalusian PSOE leader and regional premier Susana Díaz will take place at the end of March, reported El Pais Monday, making them the first of four major election dates in Spain: local and regional elections in May, Catalan regional elections in September, and national elections on a date to be determined but by the end of the year. Andalusia is the largest region in the country by population and a traditional PSOE stronghold so the PSOE hopes to have a strong showing there to set the narrative for the year’s later elections.

If a good result by Susana Díaz in Andalusia were followed by a poor result in the regional elections in May, however, it would also give Díaz a strong platform to challenge Secretary General Pedro Sánchez in the party primary to be the lead candidate in the general election. It is easy to forget that the PSOE only elected a party leader and not a presidential election candidate in the internal party contest last July. El Diario has a timeline of the simmering conflict between Sánchez and Díaz. Reportedly the “old guard” of the party is displeased with Sánchez’s tenure as secretary general so far, and has begun manoeuvering to undermine him and install Díaz instead. Díaz, however, seems to dislike primaries and would prefer to be party leader “by acclamation”, writes Vozpópuli.

The PSOE also hopes to make Andalusia the first battleground to face Podemos, whose party structure is not well developed at the regional and local level, in particular in Andalusia where it will be forced to set up a campaign structure in just 2 months, writes El País. It appears unlikely that the region’s PP will repeat its good showing three years ago, and so the regional government will depend on the correlation of forces between PSOE, outgoing coalition party IU, and newcomer Podemos.

Whelan on QE

The debate on QE continues – but is mercifully shifting into some of the more technical issues – which are the ones that matter the most. Karl Whelan has produced the best summary on QE we have seen. He touches on all the issues, including how the 25% issue limit squares up with the 33% issuer limit, and at what point the a central bank asset purchase constitutes debt monetisation – the answer is when the central bank rolls over. One most interesting part to us is whether the ECB can actually force the NCB to buy their quote, or not, and if so, whether it will actually do so. Apparently, this is not so clear. Referring to Draghi’s answer at the presser, he writes:

“This still seems to me to fall short of saying that the ECB has decided to force an NCB to buy exact amounts of specific securities. Most likely I’m wrong and the Bundesbank is about to start buying very large amounts of German government bonds but it seems like there might just be the slightest amount of wiggle room here, e.g. the Bundesbank could decide to use its QE allocation just to buy covered bonds.”

Another important discussion point on which Whelan has strong views was the agreement on risk sharing. Whelan believes the agreement is actually quite good because it solves an important problem.

“If the bonds were shared around the Eurosystem, that would greatly increase the chance that the Governing Council would use its powers to act as a de facto senior creditor (as happened in Greece). All told, this is probably the safest realistic option for private creditors concerned about default risk.”

A potentially interesting side aspect is whether any ambiguity might give the Constitutional Court some leverage over the process. If there is any wiggle room, it could order the Bundesbank not to participate, or to use any freedom of manoeuvre.

QE causes hyperinflation after all

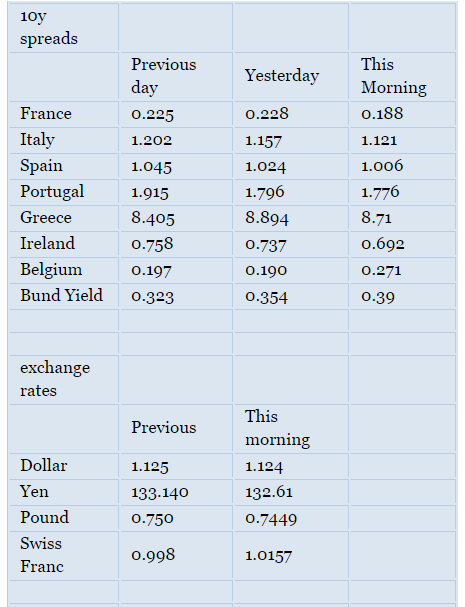

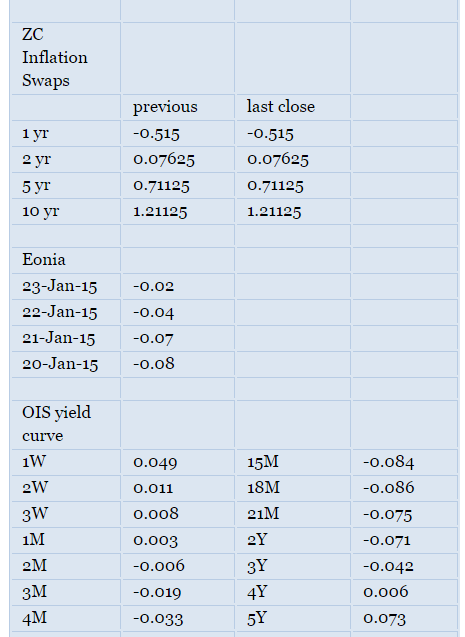

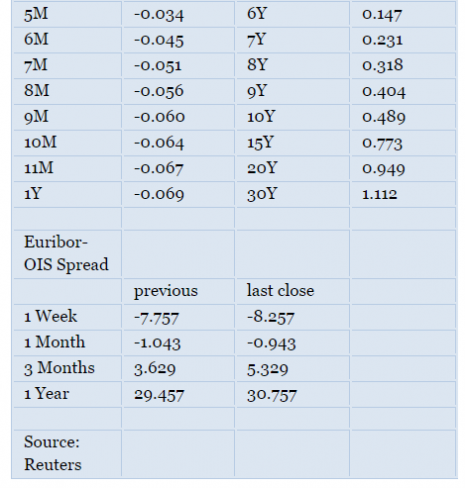

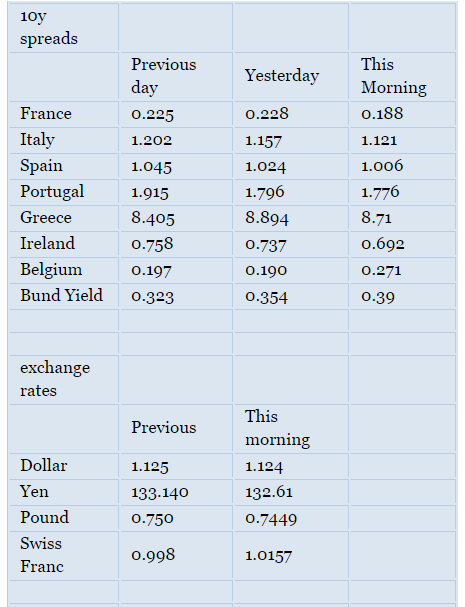

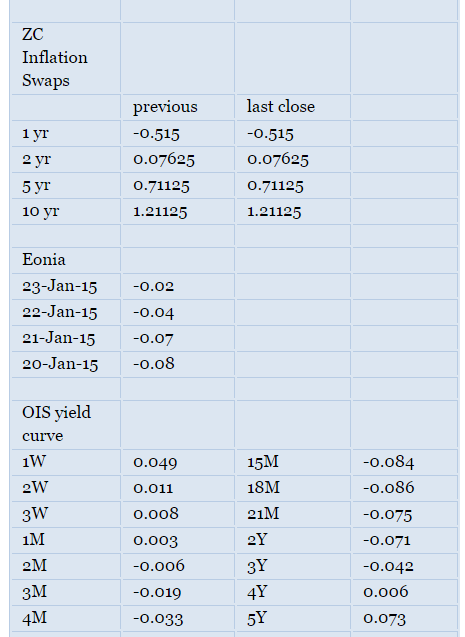

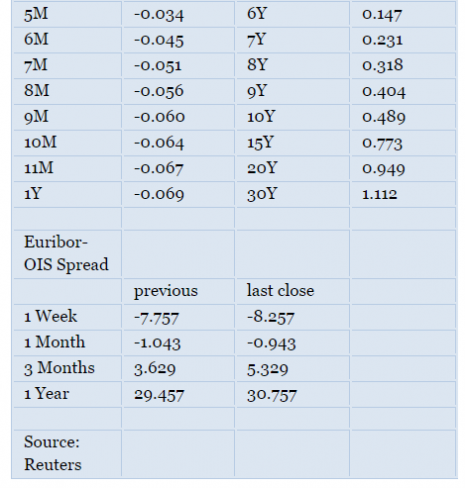

Eurozone Financial Data

→ gennaio 28, 2015

by Martin Wolf

Sometimes the right thing to do is the wise thing. That is the case now for Greece. Done correctly, debt reduction would benefit Greece and the rest of the eurozone. It would create difficulties. But these would be smaller than those created by throwing Greece to the wolves. Unfortunately, reaching such an agreement may be impossible. That is why the belief that the eurozone crisis is over is mistaken.

Nobody can be surprised by the victory of Greece’s leftwing Syriza party. In the midst of a “recovery”, unemployment is reported at 26 per cent of the labour force and youth unemployment at over 50 per cent. Gross domestic product is also 26 per cent below its pre-crisis peak. But GDP is a particularly inappropriate measure of the fall in economic welfare in this case. The current account balance was minus 15 per cent of GDP in the third quarter of 2008, but has been in surplus since the second half of 2013. So spending by Greeks on goods and services has in fact fallen by at least 40 per cent.

Given this catastrophe, it is hardly surprising that the voters have rejected the previous government and the policies that, at the behest of the creditors, it — somewhat halfheartedly — pursued. As Alexis Tsipras, the new prime minister, has said, Europe is founded on the principle of democracy. The people of Greece have spoken. At the very least, the powers that be need to listen. Yet everything one hears suggests that demands for a new deal on debt and austerity will be rejected more or less out of hand. Fuelling that response is a large amount of self-righteous nonsense. Two moralistic propositions in particular get in the way of a reasonable reply to Greek demands.

The first proposition is that the Greeks borrowed the money and so are duty bound to pay it back, how ever much it costs them. This was very much the attitude that sustained debtors’ prisons.

The truth, however, is that creditors have a moral responsibility to lend wisely. If they fail to do due diligence on their borrowers, they deserve what is going to happen. In the case of Greece, the scale of the external deficits, in particular, were obvious. So, too, was the way the Greek state was run.

The second proposition is that, since the crisis hit, the rest of the eurozone has been extraordinarily generous to Greece. This, too, is false. True, the loans supplied by the eurozone and the International Monetary Fund amount to the huge sum of €226.7bn (about 125 per cent of GDP), which is roughly two-thirds of total public debt of 175 per cent of GDP.

But this went overwhelmingly not to benefiting Greeks but to avoiding the writedown of bad loans to the Greek government and Greek banks. Just 11 per cent of the loans directly financed government activities. Another 16 per cent went on interest payments. The rest went on capital operations of various kinds: the money came in and then flowed out again. A more honest policy would have been to bail lenders out directly. But this would have been too embarrassing.

As the Greeks point out, debt relief is normal. Germany, a serial defaulter on its domestic and external debt in the 20th century, has been a beneficiary. What cannot be paid will not be paid. The idea that the Greeks will run large fiscal surpluses for a generation, to pay back money creditor governments used to rescue private lenders from their folly is a delusion.

So what should be done? The choice is between the right, the convenient and the dangerous.

As Reza Moghadam, former head of the International Monetary Fund’s European department, argues: “Europe should offer substantial debt relief — halving Greece’s debt and halving the required fiscal balance — in exchange for reform.” This, he adds, would be consistent with debt substantially below 110 per cent of GDP, which eurozone ministers agreed to in 2012. But such reductions should not be done unconditionally.

The best approach was set out in the “heavily indebted poor countries” initiative of the IMF and the World Bank, which began in 1996. Under this, debt relief is granted only after the country meets precise criteria for reform. Such a programme would be of benefit to Greece, which needs political and economic modernisation.

The politically convenient approach is to continue to “extend and pretend”. Undoubtedly, there are ways of pushing off the day of reckoning still further. There are also ways of lowering the present value of interest and repayments without lowering the face value.

All this would allow the eurozone to avoid confronting the moral case for debt relief for other crisis-hit countries, notably Ireland. Yet such an approach cannot deliver the honest and transparent outcome that is sorely needed.

The dangerous approach is to push Greece towards default. This is likely to create a situation in which the European Central Bank would no longer feel able to operate as Greece’s central bank. That then would force an exit. The result for Greece would certainly be catastrophic in the short term.

My guess is that it would also reverse any move towards modernity for a generation. But the damage would not just be to Greece. It would show that monetary union in the eurozone is not irreversible but merely a hard exchange-rate peg.

That would be the worst of both worlds: the rigidity of pegs, without the credibility of a monetary union. In every future crisis, the question would be whether this was the “exit moment”. Chronic instability would be the result.

Creating the eurozone is the second-worst monetary idea its members are ever likely to have. Breaking it up is the worst. Yet that is where pushing Greece into exit might lead. The right course is to recognise the case for debt relief, conditional on achievement of verifiable reforms. Politicians will reject the idea. Statesmen will seize upon it. We will soon know which of the two they are.

→ gennaio 28, 2015

di Michele Salvati

Quali saranno le conseguenze delle elezioni greche sui Paesi dell’eurogruppo, e soprattutto sui più deboli, nessuno è oggi in grado di prevedere: dalle prime reazioni dei mercati, delle autorità europee e dei Paesi più forti — della Germania soprattutto —, sembrerebbe esclusa una catastrofe imminente. Ma molte cose possono andare storte se il nuovo governo greco non si rimangerà gran parte delle sue promesse elettorali nelle negoziazioni con la troika. Se così non farà, e se l’atteggiamento europeo sarà poco flessibile, i rischi di guai seri saranno soltanto rimandati. Essendo troppe le variabili in gioco, guardare avanti è impossibile. È possibile invece guardare indietro e trarre qualche lezione, per noi e per i Paesi in condizioni simili alle nostre, dalla (sinora) breve storia dell’Unione monetaria europea.

Alcuni colleghi hanno trovato eccessive le affermazioni di un mio recente articolo (Corriere, 17 gennaio): che è stato un errore aderire al trattato di Maastricht e che, se fosse possibile farlo senza incorrere in costi esorbitanti, dovremmo uscire dalla moneta unica. A quell’errore ho partecipato: negli anni 90, la convenienza ad aderire al Trattato — data la situazione di inflazione latente e gli alti tassi d’interesse che eravamo costretti a pagare — mi sembrava ovvia. Non mi rendevo però conto che, nel lungo periodo, tale convenienza era legata a tre scommesse, tutte perse, dunque a tre illusioni.

La prima era che la favorevole situazione economica internazionale che accompagnò la nascita della moneta europea durasse indefinitamente. Ci eravamo dimenticati delle analisi di Keynes e di Minsky, dell’instabilità congenita del capitalismo, degli squilibri reali e finanziari che stavano montando. Quando esplose, nel 2008, la crisi finanziaria americana rapidamente si trasmise all’Europa, in un mondo ormai strettamente interconnesso i capitali cominciarono ad abbandonare gli investimenti nei Paesi più fragili dell’eurozona. Erano in euro, è vero, ma l’Europa non era uno Stato sovrano e non c’era una Banca centrale costretta a intervenire per difenderli, non c’era un prestatore di ultima istanza. Cominciò allora la divaricazione (spread) tra i rendimenti e iniziarono a crescere gli oneri a carico degli Stati più indebitati e più fragili. Già, ma perché negli anni favorevoli, tra il 1999 e il 2007, questi Stati non si erano dati maggiormente da fare per ridurre il proprio indebitamento e, più in generale, per aumentare la propria competitività?

E qui si rese evidente la seconda illusione: rimediare ai guasti di un passato di cattiva gestione economica e di debolezza strutturale non è per nulla semplice, e sicuramente non è rapido. Nelle migliori élite italiane circolò a lungo l’idea che il «corsetto» dell’euro avrebbe indotto i governanti a una gestione più responsabile delle finanze pubbliche (la famosa metafora di Ulisse che si fa legare all’albero maestro per non cedere alle lusinghe delle sirene). Si vide però assai presto, nella legislatura 2001-2006, che il corsetto non teneva e che il confortevole avanzo primario della precedente legislatura veniva rapidamente dilapidato.

Non voglio farne una questione di parte, perché dubito che un governo di centrosinistra si sarebbe comportato in modo molto diverso: troppo invitante è l’uso della spesa pubblica per assicurarsi consenso politico. Trasformare un Paese «vizioso» in uno virtuoso, quando non ci sono ragioni impellenti per stringere la cinghia, è uno sforzo politico sovrumano e richiede o un consenso sociale straordinario (quello inglese ai tempi della guerra, del «sudore, lacrime e sangue ») o un dittatore benevolo, più che un normale leader democratico. O entrambi. Ma non avrebbe potuto l’Unione — e i Paesi più forti dell’eurogruppo — venire in soccorso del Paese (temporaneamente?) in crisi e sotto attacco speculativo?

Questa è la terza illusione, la terza scommessa irrealistica, quella di scambiare il sogno di un’Europa federale con la realtà, una realtà in cui un demos europeo è molto debole, la politica è ancora largamente un affare nazionale, i sospetti e i pregiudizi dei singoli Paesi dell’Unione nei confronti degli altri sono molto forti. Se persino una parte del popolo italiano — quella rappresentata dalla Lega — protesta contro lo sforzo di mutualità richiesto alle regioni più ricche a sostegno di quelle più povere, e questo dopo 150 anni di unità politica, come illudersi che la Germania avrebbe potuto comportarsi diversamente con l’Italia?

Gli economisti si saranno accorti che mi sono limitato a riformulare diversamente parte degli argomenti secondo i quali l’Europa dell’euro non è un’area valutaria ottimale e dunque un’unione monetaria vincolante è difficilmente sostenibile. Questa è la lezione riassuntiva che i Paesi più fragili dell’eurogruppo dovrebbero trarre dall’esperienza dei quindici anni di moneta unica. La crisi provocata dalle elezioni greche può essere una occasione per ristrutturare l’intero edificio costruito a Maastricht. Una ristrutturazione che non abbisogni, per funzionare, delle tre scommesse illusorie che ho appena descritto.

→ gennaio 26, 2015

di PHILIP PLICKERT

hon zweimal hat Griechenland erhebliche Schuldenerleichterungen bekommen. Vor knapp drei Jahren, im März 2012, setzte das Land einen ersten Schuldenschnitt durch – einen „freiwilligen“ Verzicht seiner damals noch überwiegend privaten Gläubiger. Griechische Staatsanleihen im Nominalwert von annähernd 200 Milliarden Euro wurden in neue Titel getauscht. Das war die größte Umschuldung eines Staates in der Nachkriegszeit. Die Gläubiger, darunter viele europäische Banken sowie die staatliche KfW, verzichteten auf 53,5 Prozent des Nennwerts der Forderungen und erhielten neue, garantierte Anleihen mit längerer Laufzeit und einer niedrigeren Verzinsung von 3,65 Prozent.

Insgesamt sank die nominale Schuld Griechenlands um 105 Milliarden Euro. Aber der Entlastungseffekt dauerte nicht lange. Weil die griechische Wirtschaft in einer tiefen Rezession war, schrumpfte die Wirtschaft schneller als der Schuldenberg. Im Herbst 2012 lag die Schuldenquote – gemessen als Anteil am BIP – schon wieder über dem Stand vor dem Schuldenschnitt. Und seither ist sie weiter gestiegen, weil Griechenland stetig neue Hilfskredite bekam und die Wirtschaft zugleich schrumpfte.

Einen zweiten, verdeckten Schuldenerlass gewährten die Euro-Finanzminister im November 2012. Ihr Paket umfasste damals einen kreditfinanzierten Schuldenrückkauf, eine Senkung der Zinsen für die Hilfskredite und eine sehr lange Streckung ihrer Laufzeiten (um 15 auf 30 Jahre). Die letzten Rückzahlungen an die europäischen Kreditgeber sind erst 2044 fällig. Die Zinsen wurden um einen Prozentpunkt auf nur noch den Euribor-Zinssatz plus 0,5 Prozentpunkte gesenkt. Aktuell sind das also nur noch 0,6 Prozent.

Dieser zweite Schuldenschnitt brachte große reale Verluste für die Steuerzahler Europas – nur hat es kaum jemand gemerkt. Das Ifo-Institut errechnete damals, dass der Gegenwartswert der Forderungen durch die Erleichterungen um rund 47 Milliarden Euro gesunken sei, auf so viel hätten also die öffentlichen Gläubiger faktisch verzichtet, darunter Deutschland auf 14 Milliarden Euro. Allerdings sind solche Barwert-Berechnungen unsicher. Der Chef des Euro-Krisenfonds, Klaus Regling, errechnete kürzlich, dass der EFSF-Fonds durch Zinssenkungen und Laufzeitverlängerungen auf 40 Prozent seiner Forderungen verzichtet habe.

Weil die Hilfskredite nun äußerst günstig sind, kann Griechenland seine Schulden trotz der nominal riesigen Höhe recht gut schultern. Griechenland zahlt nur 4,4 Prozent vom BIP für den Schuldendienst. Dies ist weniger als etwa Portugal. Im Durchschnitt zahlen die Griechen auf ihre Staatsschulden nur 2,4 Prozent Zinsen, weniger als der Durchschnittszins der deutschen Bundesanleihen.

→ gennaio 5, 2015

Editoriale di Giuliano Ferrara

Curare i gay” è una scemenza col botto, un gesto di piccola intolleranza ignorante. Sono molto sorpreso da Costanza Miriano, una scrittrice popolare e ben disposta verso la scorrettezza connaturale alle idee; da Luigi Amicone, un ciellino che mi pare vivace e autentico; da Roberto Maroni, sassofonista e politico di talento ma ambiguo, oggi inzuppato nel nazionalismo macho dei tombini di ghisa in mancanza di meglio. Tutti abbiamo bisogno di essere curati e soprattutto di essere lasciati in pace. A tutti sono dovuti rispetto, libertà personale, privacy. La lettura del Simposio platonico o del Fedro, lo studio delle biografie di Anselmo d’Aosta e del cardinale Newman, una scorsa ai romanzi di Isherwood sono attività facoltative, e anche le tirate di s. Paolo contro i sodomiti sono le benvenute, perché parlano di peccato e non di malattia, sono illuminate dal precetto che “il giusto vivrà per la fede” e non dal positivismo burlesco della cattiva ideologia contemporanea. Invito caldamente i nominati, nel giorno del convegno lombardo al quale hanno promesso di partecipare, giorno ch’è imminente, a starsene a casa o a organizzare la protesta contro l’insegnamento nelle scuole milanesi dell’ideologia del gender o dell’indifferenza sessuale, senza dimenticare che la sola radiografia del fenomeno da parte di un prete di curia milanese ha indotto l’arcivescovo a scusarsi per l’iniziativa. Le sentinelle leggano libri buoni in piedi invece di mettere in provetta, con l’assistenza di psichiatri psichiatrizzabili e di tradizionalisti senza il senso della tradizione, chimismi, ormoni in pillola e altre vaghezze dagli scaffali del farmacista Homais. Il buco della serratura e il comune senso del pudore lasciatelo alla dottoressa Boccassini, una specialista.

Un tetro silenzio della ragione, mascherato da lago d’amore, ha preso il posto vuoto lasciato dalla generosa e apocalittica abdicazione al soglio di Ratzinger. Tutto quello che era pensiero strutturato, elegante, mite, forte e intenso, si è come volatilizzato in un batter d’occhio. Da un lato abbiamo il cedimento intellettuale di un pensatore debole come monsignor Bruno Forte, che ha sostituito Karl Barth con Roland Barthes; dall’altro l’irrigidimento caricaturale e clinicizzante dei materiali culturali non negoziabili che furono lo stigma d’intelligenza di una lunga stagione cattolica e laica del contemporaneo. Quelli della Manif pour tous in Francia hanno trovato spesso modi sensati e colorati di sense of humour per esprimere il rigetto del dottrinarismo di gender e delle teorie omosessualiste ortodosse, qui ci balocchiamo con il dottrinarismo terapeutico e altre perversioni da capofamiglia. Ma scherziamo? Ratzinger aveva spiegato in tutta la sua teologia e predicazione che il mondo moderno era diventato – esso sì – relativisticamente dottrinario, che stava crescendo come una schiuma noiosa e infeconda di pregiudizi, insultante per la fede alleata della ragione. Dottrinario sarà lei – era il suo insegnamento – i libri cristiani e il libro cristiano aiutano a pensare anche il tempo e la storia oltre le sue miserie, oltre la banalizzazione del peccato, oltre il pensiero unico, esclusivo, irregimentato. E noi vogliamo riportare la cultura cristiana e cattolica dentro le ossessioni ideologiche del tempo, mettendo la psicologia comportamentale e altre bellurie dentro la nuova evangelizzazione. Almeno andate al cinema, se siete interessati alle visioni del mondo. C’è The imitation game in tutte le sale: se avessero messo Alan Turing in un sanatorio per froci, oggi saremmo tutti sudditi del Terzo Reich, molto probabilmente.

E prendete nota della biografia di Winston Churchill scritta da Boris Johnson, il machissimo e rutilante sindaco di Londra. Raggiunsero affannati Churchill nella quiete dalla campagna mentre scriveva. Gli dissero che era stato trovato un alto funzionario del governo mentre si faceva un militare della guardia su una panchina di Hyde Park alla fine di novembre, alle tre del mattino, e che lo scandalo sarebbe scoppiato in poche ore. Churchill sollevò il capo dai fogli e chiese conferma. Era avvinghiato a una guardia? Su una panchina del parco? Alle tre del mattino? Con questo tempaccio? “Ma c’è di che rendere orgoglioso lo spirito britannico”, concluse.

→ dicembre 3, 2014

diFederico Rampini

L’Europarlamentare Andreas Schwab ora sa cosa bisogna aspettarsi per avere attaccato Google. È al centro di uno scandalo, almeno sui media Usa. La classe politica americana lo sta accusando di conflitto d’interessi. L’eurodeputato tedesco Schwab, cristiano- democratico vicino ad Angela Merkel, nonché firmatario della risoluzione parlamentare per smantellare Google, è anche consigliere di uno studio legale che difende gli editori anti-Google. Da che pulpito viene la lezione sul conflitto d’interessi? Gli Stati Uniti hanno abbassato la guardia su quel fronte, dopo la sentenza della Corte suprema che liberalizza i finanziamenti alle campagne elettorali: da allora i big del capitalismo americano non hanno più limiti nelle donazioni ai candidati. Gli stessi parlamentari americani che attaccano Schwab, possono avere ricevuto fondi da Google, mascherati nelle scatole opache dei Super-Pac (political action commette). Ma tant’è: a’ la guerre comme a’ la guerre. Tutti i colpi sono permessi, nel conflitto che oppone l’Unione europea a Google. È dai tempi dell’azione antitrust promossa da Mario Monti contro Microsoft che non si assisteva ad uno scontro così duro su un colosso dell’hi- tech americano. A Washington c’è chi minaccia ritorsioni commerciali, si parla di far saltare il negoziato sulla liberalizzazione degli scambi tra le due sponde dell’Atlantico, per reagire alla presunta “aggressione” contro Google.

L’offensiva europea ha diversi aspetti. L’europarlamento ha approvato la mozione Schwab che invoca uno “spezzatino”, lo smembramento di un colosso divenuto troppo potente: ma si tratta di una risoluzione che non ha effetti operativi, né conseguenze immediate. Il voto dell’europarlamento forse incoraggerà altre offensive europee, portate avanti da protagonisti diversi. La Commissione di Bruxelles può rilanciare l’azione antitrust. La Corte di Giustizia ha già obbligato Google a garantire il “diritto all’oblìo” per proteggere la privacy dei cittadini europei che vogliono cancellare notizie diffamatorie dal motore di ricerca. C’è la battaglia sulla webtax. Infine c’è il dibattito sullo spionaggio digitale, scatenato dalle rivelazioni di Edward Snowden, e le contromisure che alcuni governi (Germania in testa) hanno allo studio: anche questo riguarda Google poiché Snowden ha dimostrato il collaborazionismo dell’azienda digitale con la National Security Agency. Che cosa può rischiare Google? Per quanto riguarda eventuali sanzioni antitrust, i precedenti vanno dal miliardo di euro di multa contro Intel ai 3 miliardi di dollari di sanzioni “a rate” su Microsoft. I legali di Eric Schmidt, presidente di Google, temono di poter arrivare fino a 6 miliardi di dollari di sanzioni, oppure il 10% del fatturato globale, se Bruxelles optasse per la linea dura. Dettaglio interessante: tra le “parti lese” che si sono appellate all’antitrust europeo ci sono i concorrenti americani di Google, come Microsoft e Yelp. Convinti evidentemente che sia più facile castigare le prepotenze di Google a Bruxelles anziché a Washington.

Perché l’antitrust europeo può decidere di intervenire contro Google, laddove l’antitrust americano non ne ravvisa la ragione? Le spiegazioni sono tante, la più semplice è questa: il potere monopolistico di Google è effettivamente più accentuato sul mercato euro- peo. Il motore di ricerca creato da Larry Page e Sergey Brin ha quasi il 90% di quota di mercato sul Vecchio continente contro il 68% negli Stati Uniti. Un’altra spiegazione chiama in causa il nazionalismo economico. L’Europa ha una presenza marginale nell’economia digitale. I Padroni della Rete sono tutti americani, nella Silicon Valley californiana o nella sua propaggine settentrionale di Seattle. Les Gafas , come li chiamano i francesi che hanno coniato l’acronimo dalle iniziali di Google Apple Facebook Amazon. L’Europa si sente colonizzata, l’America è la colonizzatrice. Gli approcci sono diametralmente opposti. Il magazine The New Yorker constata la recente alluvione di libri di management scritti da dirigenti di Google: sono idolatrati qui negli Stati Uniti come i nuovi guru del management, i profeti da ascoltare per avere successo. Ho raccontato su queste colonne la mia esperienza ad una presentazione newyorchese del best-seller di Eric Schmidt. La folla di giovani accorsa ad ascoltarlo non era critica, tantomeno ostile: il sogno di un ventenne americano è lavorare per Google (subito dopo Apple). Politicamente questi colossi sono intoccabili. Il Congresso di Washington ha sì promosso un’inchiesta sulla maxielusione fiscale di Google, Apple & C., ma le denunce non hanno avuto un seguito concreto. I repubblicani per definizione stanno coi capitalisti e contro le tasse. I democratici sono destinatari di generosi finanziamenti, la Silicon Valley ha il cuore che batte a sinistra.

Anche in Europa c’è chi prende le distanze dalla “Googlefobia”. Il settimanale The Economist ha dedicato l’ultima inchiesta di copertina ad un’appassionata difesa di Google. Gli argomenti sono quelli classici del neoliberismo: lasciate fare il mercato, ci penserà lui. The Economist ricorda che nessun gigante hi-tech è mai sopravvissuto per più di un ciclo d’innovazioni: gli ex-monopolisti Ibm e Microsoft sono ridotti a campare su nicchie di mercato. Conclusione: gli europei farebbero meglio a creare le condizioni per avere una loro Silicon Valley, un ambiente favorevole all’innovazione e alla crescita di giganti tecnologici, invece di attaccare i successi altrui. Ma l’argomentazione neoliberista ha delle inegnuità. Dimentica il ruolo decisivo dello Stato, proprio qui in America, nel favorire i “campioni nazionali”: è la tesi dimostrata dalla economista Mariana Mazzuccato nella sua celebre ricerca sulle origini pubbliche dell’innovazione (da Internet agli smartphone).

C’è poi la battaglia per la tutela della privacy degli utenti, e delle royalty di chi crea contenuti. Anche questa è più avanzata nell’Unione europea. La spiegazione è semplice: negli Stati Uniti un trentennio di egemonia neoliberista ha cancellato molte conquiste dei consumatori. L’antitrust Usa ha le unghie spuntate da molte Amministrazioni repubblicane. Il consumerismo nacque qui negli anni Sessanta con le battaglie di Ralph Nader, ma da allora i rapporti di forza si sono rovesciati a favore del Big Business. E oggi non c’è nulla di più Big dei Padroni della Rete, Google in testa.